Trump Time Capsule #150: James Comey and the Destruction of Norms

The rules in politics haven’t changed that much in recent years. What has changed is adherence to norms, in an increasingly destructive way.

I made that case, using examples different from the ones I’m about to present here, nearly two years ago. The shift in norms is also a central part of Thomas Mann’s and Norman Ornstein’s prescient It’s Even Worse Than It Looks and Mike Lofgren’s The Party Is Over, plus of course Jonathan Rauch’s “How American Politics Went Insane,” our very widely read cover story (subscribe!) this summer.

Today’s examples:

—Before 2006, use of a Senate filibuster to block legislation or nominations was an occasional tool-of-the-minority, not a routine practice. Now it has become so routine and, well, normalized that a story in our leading newspaper can matter-of-factly say, “It actually takes 60 votes to bring a Supreme Court nomination to the Senate floor.” Actually it takes 60 votes only if there is a filibuster, which didn’t use to be normal. Inconceivable as it now seems, three of Ronald Reagan’s nominees—Justices Scalia, Kennedy, and O’Connor—were approved unanimously. Most Democrats in the Senate disagreed with some or all of their views. Not a single Democrat voted against them.

—Before February of this year, the universal assumption was that a sitting president’s nominations for the Supreme Court would be considered, although of course they might be voted down. But before the sun had set on the day of Antonin Scalia’s death, Mitch McConnell had made clear that the Senate would not consider any nomination from the 44th president, and since then John McCain and others have suggested that, depending on who becomes the 45th president, her nominations might not be considered either. (For historic reference you can see an official list here, showing relatively prompt consideration up-or-down of previous nominees.)

—Before this year, the norm through the post-Watergate era was that any major-party presidential nominee would make tax-return information public, in enough time before the election for voters to consider the implications of income sources, debts, donations, and other entanglements. Donald Trump has flatly refused, and his own party’s members barely bother to mention it anymore.

—Before this summer, sitting Supreme Court justices, no matter how evident their partisan leanings, avoided publicly taking sides in upcoming elections. Ruth Bader Ginsburg ignored that norm by saying in July how much she hoped Donald Trump did not become president. To her credit, and in contrast to these other cases, within a few days she belatedly honored the importance of this norm by apologizing for her remarks.

The official rules didn’t change in these circumstances. The norms—that is, the expectation of what you “should” do, what you “really have to do,” what is the “right thing” to do, even if the letter of the law doesn’t spell it out—have changed. For its survival, a democracy depends on norms. That’s why the shift matters.

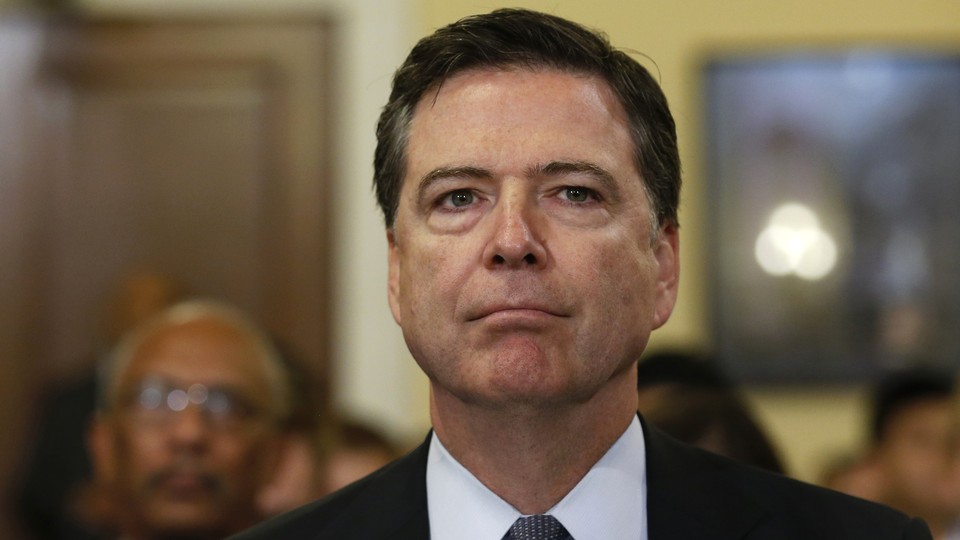

And that is the context in which I think about James Comey’s plunge into electoral politics, with his announcement about whatever “new” Clinton-related email information the FBI may or may not have found.

No one knows what this will mean for the election. Millions of people have already voted; in the nine days until official election day there’s not enough time to fully vet and consider what Comey may have found. Will the announcement re-energize Hillary Clinton’s supporters, making them worry that the race may be tightening again? Depress them? Motivate team Trump? Bolster the “they’re all terrible” case for third-party candidates?

We don’t know. But anyone experienced in politics, as Comey obviously is, would have known for dead certain that his intrusion would change the process in a way that cannot be undone. This is apparently what other officials in the FBI and Justice Department were telling Comey before he took this step. Two former deputy attorneys general—Jamie Gorelick, who served under Bill Clinton, and Larry Thompson, who served under George W. Bush—made that point in a new Washington Post essay that lambastes Comey for his self-indulgent decision (emphasis added):

Decades ago, the department decided that in the 60-day period before an election, the balance should be struck against even returning indictments involving individuals running for office, as well as against the disclosure of any investigative steps. The reasoning was that, however important it might be for Justice to do its job, and however important it might be for the public to know what Justice knows, because such allegations could not be adjudicated, such actions or disclosures risked undermining the political process. A memorandum reflecting this choice has been issued every four years by multiple attorneys general for a very long time, including in 2016. ...

They conclude that this move was so selfish on Comey’s part, potentially protecting him at the cost of broader institutional destruction:

He may well have been criticized after the fact had he not advised Congress of the investigative steps that he was taking. But it was his job — consistent with the best traditions of the Department of Justice — to make the right decision and take that criticism if it came. ...

As it stands, we now have real-time, raw-take transparency taken to its illogical limit, a kind of reality TV of federal criminal investigation. Perhaps worst of all, it is happening on the eve of a presidential election. It is antithetical to the interests of justice, putting a thumb on the scale of this election and damaging our democracy.

If either Thompson or Gorelick had been at the Justice Department now, neither he nor she would have been able to prevent Comey from making his announcement. That is, they couldn’t rely on rules. But they are arguing that he should not have done it. He should have foreseen the damage he would do, and spared a frayed democracy these destructive effects.

Last week I mentioned the ongoing cultural/“norms-enforcing” challenges that had plagued the Philippines, which I’d written about back at the end of the Marcos era in a piece called “A Damaged Culture.” The rules by which the Philippine Republic is governed are fine. A big problem involved norms—the things that powerful people did, just because they could get away with it.

The rules of American governance are still more or less OK, despite the increasing mismatch between the 18th-century structural assumptions built into the Constitution and the realities of 21st-century life. It’s time to worry about the norms.